Cambodian Zombie Apocalypse

The recent Ebola outbreak in Western Africa has been in the news for almost a year now. More than long enough to filter out to the detached settlers of my small beach.

The idea of a communicable disease that moves with such ease through small, unhygienic, communities, was terrifying to the unwashed expats and beach bums that call Otres home.

An empty sand spit six years ago, Otres Beach, Cambodia has become increasingly visible on the tourist map.

The once reclusive and tight knit community of expats and Khmer, only a few kilometers from bustling Sihanoukville, until recently felt pleasantly isolated from the troubles of the city. But progress brings conflict with those wishing to maintain the status quo. Paved roads slowly replaced dirt, bringing with it a creeping tide of crime, gangs, and most fearfully – disease.

Ebola was an African plague. A disease that affected the poorest and least easy to see. Something far removed mentally, but in reality just a flight away. SARS, H1N1 – these Asian flu’s, or a mutation of one, would more be far more likely to reach us.

Foresight, that was the buzzword around H.Q. (B.C.)

What would happen to our adopted home, and our community, should there ever be a similar outbreak? What would become of our carefully crafted oasis on the Cambodian coast?

The history of the region shows it would most likely not end well. Less than forty years removed from ethnic cleansing, the government does not have a great record of handling civil issues.

The recent explosion of HIV cases in a remote western village, later linked to reused needles, was initially explained away by the government as the result of rampant prostitution. This, despite the majority of the newly infected being small children and the elderly.

There is a quickness to turn the spotlight away from the sick and the dying. Every moment weakens the tenuous grasp the dictatorial government holds over the mindset of the poor. Any gathering, no matter how well intentioned, is feared by the administration lest it grow out of their control. Expecting government disaster aid in any way would be foolish. The greater likelihood being that information would be suppressed so as not to create a regime-shifting panic, and any foreign assistance plundered well before it reached those in need.

A group had to be convened. For the good of the Beach, the decision was made to select a hardy few to make the tough choices, the unpleasant choices, should they be needed.

The Otres Security Council (O.S.C.) met for the first time on Bastille Day, 2014.

It’s stated goal:

‘To protect the Otres community from all enemies, both foreign and domestic, but especially Zombies’

Roles were assigned, grandiose titles self applied (Vice President in Charge of Peanut Butter Hoarding, Commissioner of Looting&Sacking) and a charter loosely shouted out across the bar. Protocol taking a backseat to the sheer necessity of having a plan.

Scenario 1 – Zombies!

Outline: A secret government experiment to create ‘Triple Stuft Oreos’ backfires terribly creating an army of the undead intent on consuming every living thing. Major cities are destroyed or beginning quarantine procedures. The ratlines home for the expats residing abroad have closed. Flights are dangerous as are the cities they inevitably land in. People are told to shelter-in-place.

Response: OSC immediately initiates the previously codified ‘Zombie Survival Agreement’. This harsh but necessary piece of legislation lays out the civil rights of those living under a region dealing with an outbreak of the undead. Anyone coming in contact with infected will be quarantined in place, and if visibly bitten immediately terminated for the safety of the group. Signed and understood by all, it is our bulwark against the tide.

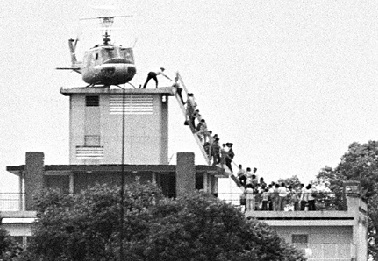

Second, the OSC begins to prepare for Operation Frequent Wind. The evacuation of key portions of the citizenry to the outlying islands – hopefully free from infection.

Operation Frequent Wind

When the last of the Americans were airlifted from the top of CIA headquarters in Saigon it signaled the end. The end of a war. The end of a superpower maybe. The folks frantically scrambling to get half a cheek on a seat in that Huey were going home. They wanted nothing more to do with their Asian quagmire.

‘You, you, and you. Everyone else wait for the next one, that may or may not be coming.’

For many here, Cambodia is home. No passports may be held, but some folks have gone fully native. The idea of leaving is as foreign to them as the French plantation holdouts in Apocalypse Now. For most there is no home to go back to. Just a vague sense of country that slowly diminishes given the right amount of time and distance.

No, our Exodus from the Beach would not be back to our respective countries – flung back around the world to go it alone. We would stay together, in our adopted land, and fight what came as one.

Exodus

A group of freethinkers, nay geniuses in the art of running away – Otres Beach has cultivated an incredible community of diversely skilled people over the years. Craftsmen, painters, and builders, the grist of the Western mill, having shirked the Union dues and endless regulation, now building their own homes, shirtless, beer in hand, smiling from ear to ear.

Science geeks mingle at the bar with philosophers, firefighters, missionaries, and mercenaries. The finest minds of my generation have filtered through, finding the place beyond the place. Some of the smartest have stayed, making lives here in the sand and mud – turning a living out of their ingenuity and sweat. If ever there was a group that could pull together some of the best of us and hide it away for safekeeping it was here.

The Security Council originally outlined two survival scenarios.

The first, in which the beach itself was barricaded, was shelved. The resources involved with adequately fortifying a large enough section of the beachhead, in order to provide for both housing and agriculture, were deemed prohibitive.

Our location, while aesthetically pleasing, was defensively tenuous. With our backs to the sea, and limited supplies or room to maneuver, we would be inevitably overrun.

The second approach, finally fleshed out as Operation Frequent Wind, advocated for a tactical evacuation by sea of up to 45 key personnel to a nearby island in the Gulf of Thailand.

The working assumption was that law and order, what little this country held, had broken down. Services such as power, sewer, and trash, while spotty without a looming apocalypse, have now stopped entirely. Law Enforcement, always a fairly voluntary pastime, will have packed up their pistols, the three bullets issued, and gone back to their home province.

Khmer Response

The Khmer reaction was a variable no one felt they could adequately predict. A panel of Anthropologists, Psychologists, and other ‘gists’, were convened to provide background.

Otres beach is bookended on either side by small, ramshackle, local shantytowns. These bustling warrens of corrugated steel and rain tarps house the 100-200 Khmer who live and work the various bars and guesthouses up and down the strip.

Incredibly poor, they work hard, in difficult conditions for one reason, money. Dollars specifically. Their own shaky currency is generally second choice. Remittances are sent back home to care for extended family in their home province.

The basic unit of cultural identity seems to be the provincial village. No matter how far from their small cluster of farms they may travel for work, or school, they maintain strong ties.

Returning to ones village periodically for illnesses, pregnancies, and layoffs is a regular occurrence. Long periods of war and famine have tightened these family units, and put them on such guard that they can draw in or prepare to move out quickly.

Any serious instability and the consensus was that most Khmer would return to their home provinces to safeguard their families. One or two families, whose working relationship with foreigners borders on familial, may opt to stay, but likely most would go.

Any serious instability and the consensus was that most Khmer would return to their home provinces to safeguard their families. One or two families, whose working relationship with foreigners borders on familial, may opt to stay, but likely most would go.

Aside from losing many dear friends, the expat residents would instantly lose the support network that keeps life possible in these remote areas.

Drinking water, carted in, quite literally sometimes by oxcart. Gasoline. Food deliveries. Everything stops. No. More. Beer.

The end of the world.

The Island

Koh Tang, a small green oasis in the deep blue of the Thai Gulf. About 54km from Otres, it can be had in a day.

Americans may recognize the name. This tiny island was the site of the final battle of the Vietnam War, known to history as the Mayaguez Incident. One last terrible misstep in a war full of them.

Days after the fall of Saigon to the North Vietnamese, the container ship Mayaguez was boarded off Koh Tang by newly minted Khmer Rouge commandos. Unbeknownst to President Ford, the crew had been quietly moved to the mainland. A hasty rescue was planned.

Thought to be lightly defended, the island was instead heavily prepared for battle, but against neighboring Vietnam instead. Hundreds of U.S. Marines landed by helicopter, many of which crashed spectacularly along the beach due to the unforseen resistance.

By the time the smoke had cleared, forty-one would be dead, three of which were left, marooned on the beach by the last retreating choppers.

The terrible irony? This seemingly poetic bookend battle to an an otherwise backwards war, was launched hours after the release of the hostages.

The military POW-MIA bone-team regularly visits the island to vainly try to identify remains, but I would assume these visits would become less regular after the Zombie Apocalypse.

It seems the perfect place to have our own final battle – the battle against nature.

Survival

The Otres Navy – formed by the O.S.C, consists of three wooden Khmer fantail boats. Tourist transporters, they each seat fifteen comfortably plus a small amount of gear. Four 18ft Hobie catamarans are kept in reserve down the beach at the fancy resort, ready for piracy should the need arise. Their sail power being necessary once the fantail boats have exhausted what little gasoline can be collected and carried.

Forty five people. That was the maximum number of evacuees the OSC plan allowed for. A constant balance had to be found between a variety of factors – weighing the benefits of group strength against higher food and water requirements.

Assuming a stay of one year, the perceived amount of time for the world to have begun righting itself, the survival of the refugees would depend on their ability to work together to provide in the harsh environment. Enough manpower would be needed to fell trees, build shelter, till soil, hunt, and most crucially – make water.

Solar stills, made easily from material brought along, should be able to supplement the ample rainfall. Evaporation stills, made from trenches filled with seawater, covered with tarp, and left to heat in the sun – if done properly, the condensation should be salt-free.

The distillation of enough water for drinking and cooking for that many people would require teams working nearly around the clock. Many hands would be needed to handle this vital chore as well as the niceties like shelter and food.

The large interior of the island could be cleared over time, and arable land made available in a limited way. If any Khmer had made the trek, then their intrinsic knowledge of the land and it’s animals would be invaluable. While we would most likely retain more than a few agricultural specialists, the peculiarities of the growing seasons here would require a local touch.

Assuming we made it beyond the limited resources we could squirrel away, the rest would be our time. Time to rebuild. Reform what community we had lost. Try, somehow, to do it better next time.